Media Guide: The Iran-China Strategic Partnership

/By AIC Senior Research Fellow Andrew Lumsden

Please note that an update to this article is available here: https://www.us-iran.org/resources/2022/3/1/media-guide-china

Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian marked his first visit to China as Foreign Minister on January 14, 2022 with an announcement that a 25-year ‘Comprehensive Strategic Agreement’ (CSP) between Tehran and Beijing, signed in 2021, would now come into effect. On January 16, Iran announced that its government ministers were in talks with their Chinese counterparts to begin drawing up contracts.

The CSP has been met with celebration among Iran’s leadership, controversy among the Iranian public and concern in the West. This Media Guide will explore the Iran/China CSP, what each side hopes to gain from the deal, reactions and possible ramifications for Iran.

What Has The Sino-Iranian Relationship Been Like Historically?

Being two ancient civilizations in relatively close proximity to each other, China and Iran have a history of close political and economic interaction dating back well over a thousand years. Coins from the Persian Sassanid Empire (224-651) have been found all over China, and some Persians, including members of the Sassanid royal family and nobility fled to China in the 7th century following the Arab conquests, and attempted to gain Chinese support for a reconquest of their country. During the Yuan (1271-1368) and early Ming (1368-1644) periods, maritime trade between China and the Iranian port city of Hormuz was common, and the city was visited more than once during the expeditions of the Chinese explorer and diplomat Zheng He.

Modern diplomatic relations between the two nations began in 1920. The relationship would sour after the communist takeover of China in 1949, as Iran’s monarchy was staunchly pro-Western. Amidst a thaw in U.S./China relations, Iran recognized and established formal diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1971. Despite some tensions after Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, Sino-Iranian relations deepened beginning in the 1980s, particularly as Tehran became increasingly isolated diplomatically and economically from the West.

Today, China and Iran have generally positive relations and hold similar outlooks on global politics. Both are authoritarian states with strained relations with the United States and its Western allies, looking to grow their own political and economic influence in a rapidly evolving global environment.

What Is The ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’?

It should first be understood that “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” is not a term unique to the recent Iran/China agreement, but rather a more general term used by Beijing to reflect the level of bilateral cooperation between China and another country. A CSP is considered the highest level of diplomacy whereby both sides promise significant, long-term political, economic, scientific, technological and cultural collaboration. In addition to Iran, several countries in the Middle East and beyond have CSPs with China including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Australia and Russia.

Initial Framework

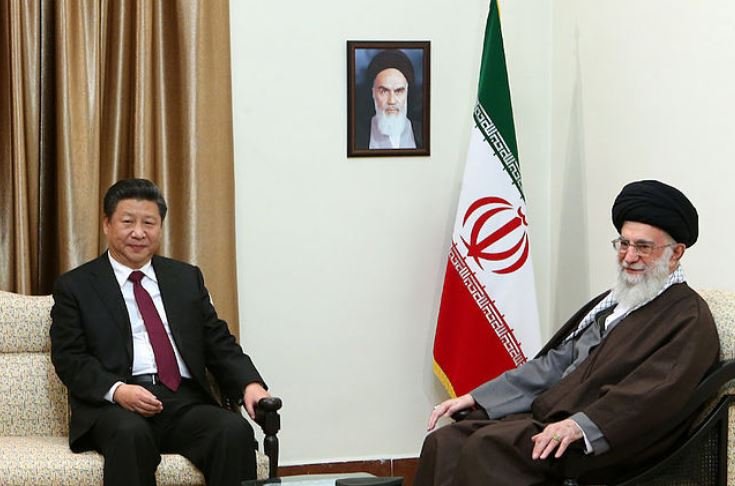

The China-Iran Comprehensive Strategic Partnership has its roots in Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s visit to Tehran in January 2016. Xi and then Iranian President Hassan Rouhani determined that an “upgrading” of Sino-Iranian bilateral relations would be necessary to preserve and achieve “peace, stability and development in the [Middle East] region and the world at large,” given the “deep and complex developments” in regional and global politics.

The two leaders released a draft framework for an agreement on a new strategic partnership, outlining Beijing and Tehran’s goals and highlighting areas for cooperation. The 2016 draft was organized according to five overarching themes, or “domains”, each with proposed courses of action:

The “Political” Domain

Tehran and Beijing agree to extend political and rhetorical support to each other. Tehran reaffirms its support for the ‘One-China Policy,’ which refers to Beijing’s assertion that Taiwan is a part of China, not a separate nation. China, for its part, expresses support for Iran having a greater influence in “regional and international affairs.”

Specific proposals include:

Annual meetings between Iranian and Chinese Foreign Ministers

Expanding relations and bilateral interactions between provincial and local governments as well as national legislative bodies in the two countries

The “Executive Cooperation” Domain

Iran pledges its support for China’s ‘Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ Initiative; a 2013 project initiated by Beijing aimed at creating new maritime and overland trade routes between China, Europe and Africa.

Specific proposals include:

Expanding investment and “tangible cooperation” in the fields of banking, mining, transportation, communications, space, manufacturing industries, railway and port development, agriculture, food, water and environmental protection

China will “consider financing and investing” in Iran’s energy sector, while Tehran will “provide the necessary facilitations and support”

The “Human and Cultural Domain”

Partly in recognition of their “historical commonalities,” Beijing and Tehran agree to encourage tourism and other forms of social interaction between the people of both countries.

Proposals include:

Increasing cooperation between media agencies in both countries, including mutual visits by media delegations

Expanding communications between Chinese and Iranian Non-Governmental Organizations and exploring the possibility of opening cultural centers

Enhancing academic cooperation through exchange of professors and students, transfer of new technologies and execution of joint projects

The “Judiciary, Security and Defense” Domain

Iran and China agree that “terrorism, extremism and separatism” threaten “all humanity and the global peace,” and vow “firm and integrated” measures to combat these “three evil forces.”

Proposals include:

Enhancing bilateral cooperation between law enforcement agencies, including in training security personnel, and devoting greater effort and resources to combating illegal border-crossing, drug smuggling, cybercrime and organized crime

Expanding bilateral judicial cooperation and consultation, including in the area of extradition

Upgrading cooperation between both countries’ armed forces and Ministries of Defense, through training, intelligence sharing and technology/equipment transfer

The “Regional and International” Domain

Both countries express their support for the “multi-polarization” of the international system. Multipolar refers to a situation in which there exists in international politics, several great powers of relatively equal political and economic strength. Since 1945, it has been argued that global politics have been ‘bipolar,’ with the U.S. and the Soviet Union monopolizing power during the Cold War, and ‘unipolar’ since the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

China expresses its intention to support Iran for full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a group of eight states (China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Pakistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) with a focus on regional security and economic development

See here the full text of the 2016 framework

“Final Draft”

In June 2020, a document allegedly from Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs titled “Final Draft of Iran-China Strategic Partnership Deal,” was leaked. This draft included the provisions outlined in the 2016 framework with additions and specifications including:

Announcement that the agreement is valid for 25 years

China’s expression of its intent to become a “steady importer of Iranian crude oil” with the expectation that Tehran will “be mindful of Chinese concerns regarding its return on investment in the Iranian oil sector.”

Specific references to proposed Chinese investments in constructing power plants and new suburban towns in Iran

Plans to facilitate Iranian natural gas transfers to China via Pakistan

Proposed joint Sino-Iranian investments in reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria

Plans to develop Iranian ports including Jask and Chabahar

Plans to develop new free trade and special economic zones in both countries and expand Iranian access to Chinese special economic zones

There have been reports that the CSP involves US$400 billion of Chinese investment in Iran. However, there is skepticism among analysts on the veracity of this figure.

The Iran/China Comprehensive Strategic Agreement was approved by Iran’s cabinet on June 21, 2020 and formally signed by both parties on March 27, 2021. Neither Tehran or Beijing have released full details about the deal and China’s Foreign Ministry has refused to confirm specific figures. However, The New York Times reports that the text of the deal was “largely unchanged” between the leak in 2020 and the final signing.

What Does Tehran Hope To Gain From Closer Ties With China?

The CSP appears to be a pronounced departure from Iran’s longstanding foreign policy mantra of “Neither East nor West,” a slogan used by the Islamic Republic’s first Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who derided the West for its support of the monarchy and history of exploitation of Iran, and Eastern powers such as the Soviet Union and China for their persecution of Muslims.

Iran’s engagement with China has hitherto been relatively limited, including in purely economic matters. Why then, at a time when China’s economic health and international reputation fall far short of what they were in recent years, is Tehran pursuing such a massive expansion and reconfiguration of its relationship with Beijing?

Iranian leaders have been quite clear about what they hope to achieve with the CSP. They have two primary objectives.

Negate the Impact of Sanctions

Since the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018, Tehran has had tremendous difficulty in securing trade and investment relationships with most countries. Between 2017 and 2019, foreign investment to Iran plunged from about US$5 billion in 2017 to a 15-year low of US$1.5 billion in 2019. Iran sees the CSP as a means of circumventing U.S sanctions by potentially securing billions of dollars in Chinese investment and a stable trade relationship with the world’s second largest economy for the next 25 years. Then-President Hassan Rouhani said in 2020 that the CSP represents “an opportunity to attract investment in various economic fields, including industry, tourism, information technology and communication.”

Hossein Nooshabadi, a member of Iran’s Parliament who also sits on the legislature’s National Security and Foreign Policy Committee, boasted that the CSP will allow Iran to “thwart” Western sanctions and noted that Tehran’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which China will enable, will open up new trade, and banking opportunities with other Asian economies as well. Hossein Hosseinzadeh, chairman of Parliament’s Oil and Energy Committee, claimed that the CSP is already leading some European states and oil companies to consider resuming business with Iran.

Some Iranian officials argue that the CSP will alleviate U.S. sanctions in another way, by pressuring the West to quickly reach an agreement on restoring the JCPOA, a 2015 nuclear deal between Iran, the U.S., UK, France, Germany, Russia and China which relieved some sanctions in exchange for limits on Iran’s nuclear program. The U.S. withdrew from the deal in 2018, but is currently in talks with Iran and the other JCPOA parties on a possible re-entry.

Ahmad Amirabadi, another Parliamentarian, who chairs the Iran and China Parliamentary Friendship Group, argues that the CSP is Tehran’s “deadline” to the West to lift sanctions, “as soon as possible.” Amirabadi believes that the U.S. and other Western powers will feel “threatened” by the CSP and ultimately be forced into “retreating” from their current stances on Iran. Similarly, MP Ardeshir Motahari, says that closer ties with China will both “reduce the impact of [U.S.] sanctions” and allow Tehran to negotiate with the West “from a higher position.”

Weakening the U.S.’ Regional and Global Influence

Iranian leaders have also expressed a vision of the CSP, and greater Sino-Iranain cooperation in general, as means of politically undermining the United States and aligning Tehran with emerging global powers. Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, the Speaker of Iran’s Parliament said that he sees the deal as an “important warning” to the United States about the decline of its global power and a reflection of the 21st century as “Asia’s century.” General Ali Shamkhani, secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council was more blunt, asserting that the “flourishing of strategic cooperation” between Iran and China is “accelerating the U.S. decline.” MP Motahari makes this argument as well, noting that “most neutral experts acknowledge the withdrawal of the world from the unipolar system,” and that China’s military power, economic clout and membership on the United Nations Security Council make forging a stronger relationship with Beijing part of Iran’s “national interests.”

What May Beijing Hope To Gain From Closer Ties With Iran?

Iranian leaders have made clear their reasons for seeking closer ties with China. However, Beijing’s motives for supporting a more intimate relationship with Iran, a heavily sanctioned, diplomatically isolated country in a volatile region, are perhaps less straightforward.

Securing Its Oil Supply

Increasing Iranian oil production capacity and facilitating the flow of Iranian fossil fuels to China are themes which feature prominently in the text of the CSP. This is a clear indication that meeting its growing energy needs is a key motivation for Beijing in its expanding relationship with Iran.

China is the world’s second largest consumer of oil, and has in recent years become increasingly dependent on foreign imports. In 2009, China imported about 4 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil. By 2019, that figure had more than doubled, slightly exceeding 10 million bpd. Between 2005 and 2014, Iran was China’s third largest oil supplier. It fell to sixth in 2015, though not due to a reduction of Chinese imports from Iran, but rather a surge of purchases from other suppliers including Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

The CSP guarantees China a steady flow of Iranian oil for at least the next 25 years, oil which will reportedly be provided at “heavily discounted” rates. Moreover, as Jon B. Alterman, Director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies notes, relying on Iran for oil as opposed to its other suppliers may in itself be a strategic move by Beijing. Beijing may see Iran, a staunch adversary of the U.S., as far less likely than many of its other oil suppliers such as Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates, to participate in any attempts to reduce China’s access to oil in the event of escalated tensions or war with the West. It should also be considered that although China’s largest oil supplier, Russia, is also a U.S. adversary, its oil reserves are smaller than Iran’s, and Sino-Russian relations are far more complicated than often portrayed in analyses of international politics.

Weakening the United States

There is a concern among U.S. officials that China also sees the CSP as a means of politically weakening the United States. According to a June 2021 report by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (abbreviated as USCC), China believes that by strengthening Iran, it can prevent Washington from “fully focusing its military, diplomatic, and economic attention” to the East Asia and Pacific regions, where Beijing’s strategic geopolitical interests primarily lie.

As AIC discussed in its Media Guide on the Iran/Saudi Arabia proxy conflict, despite a handicapped economy, Tehran has for decades provided financial, tactical and armaments support to Shi’a and other governments and militant groups friendly to its interests across the Middle East and beyond, as means of expanding its influence and undermining that of its Saudi, Israeli and American adversaries.

The U.S. fear is that an Iran strengthened and shielded by Chinese economic and military investment, will escalate its political maneuvering in the Middle East, leading to greater destabilization and forcing the U.S. to dedicate more financial and military resources to the region. As Alterman illustrated in testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, “if the United States puts two carrier strike groups off the coast of Iran, …that means that the United States only has one it can dedicate to [countering] China.” Some Chinese officials such as Hua Liming, former Chinese ambassador to Iran and Shi Yinhong, advisor to China’s State Council, have also highlighted the benefit to China of protracted U.S. entanglement in the Middle East.

Hudson Institute Fellows Michael Doran and Peter Rough, add that by helping Iran keep the U.S. entangled in Middle East politics, Beijing reaps the added bonuses of making the U.S. appear increasingly feeble and moribund as a global power when it inevitably faces failures and setbacks in the region. Meanwhile, growing bipartisan public support in the U.S. for Washington to leave the Middle East altogether would allow Iran and China to fully fulfill their regional aspirations.

Gaining Strategic Military Bases

Some analysts argue that Beijing may be using the CSP as a prelude to an expansion of China’s military presence in the Middle East. James Phillips, a Senior Research Fellow at The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank, cites the case of Djibouti, a small Eastern African country bordering the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, two strategic waterways. Phillips notes that Chinese investment in developing a port in Djibouti later resulted in Beijing gaining a military base in the country, which now houses about 1,000 Chinese troops and several warships. Chinese troops in Djibouti have reportedly attempted to sabotage and infiltrate U.S. military operations in the region. Phillips argues that the proposed Chinese investments into the Iranian port at Jask in the Gulf of Oman, a major artery of global oil transport, could evolve into a Chinese naval facility.

Doran and Rough share this view and argue that with naval bases in Jask, along with existing facilities in Sudan and Djibouti, China could effectively turn the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman into “Chinese lakes” and control the ability of nearby countries to export or import oil. However, the USCC’s report downplays China’s military interest in the Middle East, emphasizing instead Beijing’s “desire to free-ride” on the U.S. role as a responder to instability in the region.

How Have Iranians Reacted to the CSP?

Iran’s political leaders have taken an overwhelmingly positive stance on the CSP. Following the release of the framework in 2016, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei called the deal “totally correct and endowed with wisdom.” Mohammad Javad Zarif, who was Iran’s Foreign Minister when the deal was created and signed, called the agreement “historic” and Beijing a “friend of difficult days.” Current Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian, in a January 2022 op-ed for Chinese media, labeled the deal as having helped to “[pave] a new way for the second half-century of [Iran-China] relations.” Abdollahian also said that China and Iran “will be on the right side of history, forever.”

The CSP however, has not been without its critics. Former President Mahmoud Ahmedinijad blasted the Rouhani administration, accusing it of acting like “the owner of the country” in making the deal with China “without the knowledge of the nation,” and of potentially giving to a foreign power, “from the nation's pocket.” Former Reformist Parliamentarian Mahmoud Sadeghi, questioned why a deal was being made with China, when Beijing allegedly owes Tehran billions in unpaid oil bills. It has been reported that Beijing has not been paying for Iranian oil, but instead putting the value towards Iran’s debts to Chinese state oil companies which have invested in the country. Former conservative MP Ali Motohari criticized Tehran making a deal with China in light of Beijing’s treatment of its Uighur Muslim population, which in recent years has been subjected to mass incarceration, torture and destruction of religious and cultural sites, among other abuses.

The deal also elicited outcry among Iranian activists and the public. In October 2020, a group of 74 Iranian civil, political and students’ rights activists wrote an open letter to world leaders and the United Nations condemning the CSP, warning that closer ties between the “totalitarian” governments of Beijing and Tehran would constitute a “significant strategic threat to world peace and stability," as well as have “many catastrophic consequences for the Iranian people.”

Demonstrations erupted in Tehran and other major cities across the country following the CSP’s signing. Protestors chanted slogans such as “Iran is not for sale!” Online, some commentators likened the CSP to the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay in which Iran ceded much of its territory in the Caucuses to Tsarist Russia. Others expressed fears that the CSP will result in the dumping of Chinese waste in Iran, the transfer of Iranian islands to Chinese control, a Chinese military presence in Iran, flooding of Iranian markets with Chinese products and an influx of Chinese workers to Iran. The head of the Iranian Chamber of Commerce’s Commission on Mines has expressed concern over how much access Beijing will have to Iran’s minerals, saying “we should not devote our interests to countries like China and Russia.”

What Ramifications May The CSP Have For Iran?

As Tehran’s leaders believe, the ability to circumvent Western sanctions and access billions in investment funds and technology transfer and a trade relationship with China and other SCO members secured for the next several decades would certainly be of great benefit to the country. However, there are some risks which should be considered.

Civil Unrest

Though the validity of many public and online criticisms of the CSP is suspect, the deal has already resulted in some level of civil unrest in Iran, in the form of small protests. Developments in other parts of the Global South suggest that the deal’s fulfillment could result in greater expressions of popular anger.

China’s business practices in developing countries have in recent years come under intense scrutiny. The Chinese state and Chinese firms undertaking investment projects across the globe have been accused of “heavy reliance” on imported Chinese workers; providing “inadequate” employment opportunities for locals, wage and housing discrimination, seizure of land and installations as payment for debts, physical abuse, flouting labor laws and unions, population displacement and degredation of local environments and disregard for local communities.

Pro-China commentators counter that injustices such as these are isolated incidents and are not properly representative of China’s overall business practices. Nevertheless, unjust Chinese practices, real or perceived, have led to anti-China civil unrest even in countries with very close political relationships with Beijing such as Russia, Laos, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Given that the CSP has already sparked protests in Iran and perceptions that the state was ‘selling out’ to China, if any of these abuses take place in Iran amidst increased Chinese engagement, it could easily instigate larger scale anti-government sentiment and demonstrations.

U.S. Backlash

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the CSP has caused some alarm among politicians and analysts in the United States and beyond. In March 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden said that he has been “concerned” about the CSP “for a year.” While some Iranian officials have celebrated Western unease over the deal, the possibility exists that pursuing closer ties with China may result in a backlash from Western leaders, particularly the Biden administration, which is under increasing pressure from American conservatives, and some liberals, to take a harder line against both Tehran and Beijing.

The term “axis,” of Second World War infamy, has been re-emerging among some analysts as a descriptor of the burgeoning relationship between China and Iran (sometimes including Russia). In March 2021, the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board called the CSP a pact made “at the expense of the U.S. and stability in the Middle East,” blasted former President Barack Obama and President Biden for pursuing diplomacy with Iran and urged Washington and its allies to drop “illusions about the designs of their adversaries.”

Phillips from the Heritage Foundation and Bradley Bowman and Zane Zovak of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies all urged the U.S. to respond to the CSP by expanding military, including armaments, support for Iran’s regional adversaries such as Saudi Arabia, whose official media has also raised concerns about the CSP.

On the political front, the Biden administration has faced pushback from Congressional Republicans and some prominent Democrats over willingness to negotiate with Iran and re-enter the JCPOA. On February 1st, Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ), Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations cited Sino-Iranian cooperation as one of the reasons he is skeptical the nuclear deal can be revived and argues that President Biden must “rigorously enforce” U.S. sanctions on Iran and “Chinese entities” which do business with Tehran “in a way that will impose a serious cost.”

With its dealings with China, Tehran risks provoking the West, not to ‘retreat’ as MP Ahmad Amirabadi suggests it will, but to maintain and even escalate sanctions, as well as strengthen Iran’s regional opponents economically and militarily.

Disappointment

Some analysts have expressed skepticism that the CSP will have much of an impact on Iran at all, given that it is hardly guaranteed China intends to fulfill its end.

Despite itself having a very poor political relationship with the United States, China has to a large degree been respectful of U.S. sanctions on Iran. In 2019, after then-U.S. President Donald Trump formally re-imposed sanctions and all waivers expired, China’s state-run oil company CNPC withdrew from a US$4.8 billion planned joint project to develop Iran’s South Pars gas field. China also has reduced overall trade with Iran since sanctions were reimposed. In 2019, China’s exports and imports to and from Iran were slashed by a third.

Beijing also made cuts to its purchases of Iranian oil. Between 2017 and September 2018, China imported about 630,000 barrels per day (bpd) of Iranian oil. It cut its imports to about 250,000bpd in October 2018; they then declined until reaching zero in April 2020. It is important to note however that China has been defying sanctions and purchased Iranian oil through clandestine means. Throughout 2021, China purchased an estimated average of about 500,000bpd of Iranian oil. In January 2022, Beijing officially admitted to purchasing 260,312 metric tons of Iranian oil the previous December. Assuming the accuracy of these estimates, even in secret defiance of U.S. sanctions, China’s imports of Iranian oil still lag far behind their pre-sanctions levels.

China’s open defiance moreover, has largely taken place amidst a change in Washington. The Biden administration so far has not taken enforcement action against Beijing. Given Beijing’s prior willingness to scale back its dealings with Iran when risks from U.S. sanctions arise, and the fact that China enjoys a trade relationship with the U.S. worth more than 15 times that of its pre-sanctions trade with Iran, the likelihood of China suddenly making massive investments in open defiance of U.S. sanctions, particularly if the U.S. decides to begin rigid enforcement of sanctions, is questionable.

In addition to sanctions, if it were to fully honor the CSP, China may risk alienating Iran’s other enemies, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Israel with which it has a total of over US$100 billion worth of trade and many investments. As The Diplomat contributor Nima Khorrami argues, “Iranian officials are in for a bad surprise” if they believe that China would support any attempts to expand Tehran’s influence at the expense of other regional powers.

Conclusion

Amidst the abundant punditry surrounding the Iran/China CSP, the fact remains that it is simply too early to conclude whether or not the CSP will have a significant impact on either country, the United States or global politics generally. Many details about specific plans, projects and figures entailed in the CSP remain publicly unknown and perhaps unformulated, and China’s past lackluster approach towards investing in Iran and defying U.S. sanctions call into question the extent to which the deal will be implemented at all.

If it is indeed the case that Beijing and Tehran are serious about cooperation at the level described in the CSP, it is important, and ultimately best for both sides. that their focus lie with how this agreement can meaningfully benefit the people of both nations as opposed to how it can reshape the international political order or frustrate the West.