A Brief Walkthrough Pre-Modern and Contemporary Persian Art

/By AIC Research Associate Nicholas Turner

Pre-Modern Persian Art

Iran has one of the oldest cultures in the world and, subsequently, has one of the world’s oldest image making traditions. Pottery from Susa (Fig. 1), an ancient city near the Iraq border, and the site of present day Shush in Khuzestan Province, has been dated circa 4000 BCE. Surviving works from classical antiquity, starting in the 6th century BCE and ending in approximately the 5th century CE, largely come in the form of Achaemenid dynasty metalwork, pottery, and bas-reliefs such as the ones that appear on the staircase to the Apadana hall at Persepolis (Fig. 2). The Persian cultural identity remained salient during the Muslim conquest, which occurred during the first half of the 7th century, continuing to produce intricate pottery, metalwork, and stonework, as well as incorporating the Islamic epigraphic style into architectural and ceramic works. The saliency of Persian culture during this time is evidenced by early works of Islamic art which are so influenced by the Persian style that in many instances it’s difficult to not mistake Islamic works for Sasanian era pieces. Images of the warrior king and the lion (Fig. 3) were common in early works of Islamic art, and these come directly from the Sasanian tradition. The absorption of the Islamic style into the Persian tradition by contrast, can be seen largely in architectural decorations. Islamic geometric design in stucco, tiling, and carvings became commonplace, and it was this kind of art that was most accessible to the masses. The epigraphic style of Islamic art appeared on pottery and metalware towards the end of the millennium, but these works, as opposed to the architectural decorations, were primarily accessible to more affluent members of society.

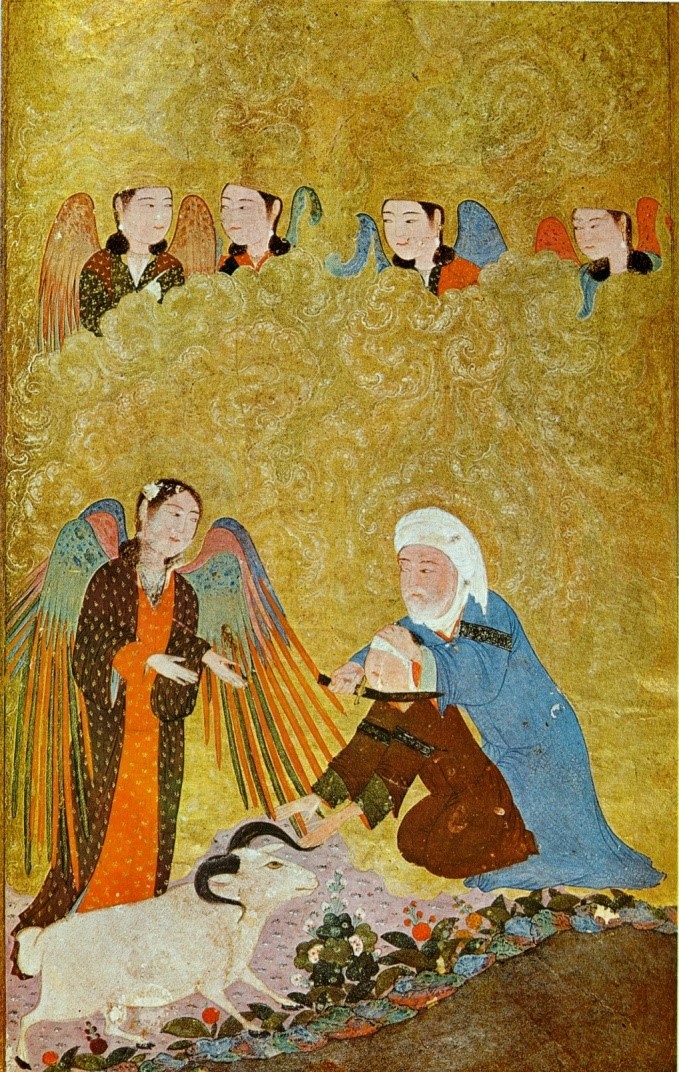

The history of pre-modern Persian painting is difficult to distill because of the fragmentary nature of the history of the medium. Much of the painting done prior to the invasion of the Mongols has been lost to time or to invading civilizations. What we do know, from pieces that remain and from the relatively well kept literature from the time, is that in the Middle Ages, figurative wall paintings were the primary genre of painting, and that it was generally the more affluent in society who were able to enjoy these works in their homes. The invasion of the Mongol’s had a schismatic effect on Persian society, especially in the realm of art and culture, which is why, along with the pieces themselves, the history and knowledge of authorship of the art prior to the invasion of the Mongols is lost. What is known as the “golden age” of Persian painting began in the 14th century during the reign of the Turko-Mongol Timurids. During this time the art of the book was refined; calligraphy was developed further and the miniature became a notable genre (Fig. 4). The miniature – one of Iran’s most well-known artistic products -- is a highly figurative genre of painting, and most miniatures were created with the purpose of illustrating scenes in a story, like Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. The Timurids brought influence to the genre with the ethnicization of the figures so that they appeared more like Central and East Asians (Fig. 5), as well as reforming the layout standards of the manuscript pages to better emphasize harmony between the text and the images. Though the earliest miniatures which remain today were produced under the Timurids, the style has existed for at least a millennium prior to the Mongol invasion. The artist and prophet Mani was creating figurative paintings back in the third century. The faith he lead, called Manichaeism, heavily employed the miniature style in their religious texts, though none of them survive today. The style has remained relevant for centuries, and a number of contemporary artists drawn on or reference the style in their works.

Bridging the gap between these ancient dynasties and modernity was the penultimate royal family to rule Iran, the Qajar dynasty. The Qajars helped set the stage for the transition to modern art in Iran. Though oil painting had existed in Iran prior to the Qajars rise to power, the family brought the medium to prominence. The early Qajar rulers like Fath ‘Ali Shah devoted time and resources to the definition of the Qajar’s royal image. This meant the commissioning of formal portraiture, and other oil paintings, for the amplification of the Shahs’ power. Under the Qajar’s Muhammad Ghaffari, the painter known as Kamal-ol-molk, came to prominence and his emphasis on formal painting solidified the continuity between Mongol era figuration and modern era realism.

Contemporary Persian Art

A modern art movement emerged in Iran in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s following the death of Iranian painter Kamal-ol-molk (Fig. 6) in 1940. His death represented a symbolic end to a rigid adherence to formalism and realism in painting, two principles which Kamal-ol-molk had championed during his life as a painter in the Qajar court. This modern movement, though it did engage with ideas that were being employed by western modern artists, was firmly grounded in Iranian artistic and cultural history. Marcos Grigorian (Fig.7), one of the most important Iranian artists of this time, used natural materials in his work, making reference to Iran’s natural landscapes and “indigenous dwellings.” Other artists like Parviz Tanavoli, drew on Iranian art’s epigraphic history with his manipulation of cuneiform and the Persian vocabulary. Tanavoli’s most well-known works come from his “Heech” sculpture series (Fig. 8). Tanavoli’s metal sculptures take the Persian word “Heech,” which means nothing, and abstracts its form into playful and emotive shapes.

Artists that grew to prominence domestically during the 50’s and early 60’s quickly broke onto the international stage during the 60’s and 70’s. Iran played host to a number of international art events and fairs during these years. Between 1958 and 1966, the Pahlavi government held five biennials in Tehran. Despite the alienating effect the Shah’s western facing regime had on a number of Iran’s people, the relative prosperity that the country experienced during this time in conjunction with the Shah’s internationalist policies lead to a boon for the country’s artists during these decades. In 1977 the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was founded, which holds an impressive collection of Iranian art as well as the largest collection of Western modern art outside of Europe or North America. A number of artists who came to the fore between the 50’s and 80’s remain relevant to this day. Works by Tanavoli have fetched prices nearing three million dollars in the last decade.

The Iranian world of visual arts was rapidly gaining steam in the third quarter of the 20th century, but the Islamic Revolution in 1979 broke the momentum the art world was enjoying. Following the revolution, the Ministry of Culture and Art and the Ministry of Information and Tourism merged to create the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance. The purpose of the Ministry is to restrict access to media that is out of line with Islamic moral values; the institution deals with visual culture such as studio art, films, and theatre. Following the revolution, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art’s large collection of Western art was stored away. It wasn’t until 1999 that the collection was seen again in an exhibition of major Western artists like David Hockney and Andy Warhol. Subject matter that is deemed immoral, the most obvious example of which is nudity or displays of sexuality, is restricted from being shown to the public, which is why a large part of TMoCA’s Western collection will never get to be shown while the Ministry maintains its position.

Additionally, content that is critical of the government can, and often is, prohibited from being shown. The Ministry’s foundation, and the restrictiveness it imposed, is one part of the reason for the slowdown of Iran’s art world following the revolution. However, this is only a piece of the explanation, and some would argue that the government’s restrictiveness sparked renewed creativity and resiliency among artists. Iranian cinema, for one, has had many achievements even since the revolution. While Iranian films first came to be held in high regard during the days of the Iranian New Wave (a movement that started in the 1950’s) (Fig. 9) this esteem for Iranian cinema wasn’t lost in the international sphere in the following decades. Filmmakers like Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Abbas Kiarostami, and Jafar Panahi all got their start in these decades following the revolution, and during this time won a number of awards at international film festivals. Panahi is a particularly compelling example of an artist who has worked around severe government imposed restrictions, having been sentenced to house arrest in 2010 and receiving a 20 year ban from filmmaking for his production of films like Offside (2006). In Offside he shot women sneaking into a World Cup match in 2006 in Iran, an event that women were barred from entering. Despite his ban on filmmaking, Panahi has produced five films since 2010, often times with content critical of the government. Though it is often an uphill struggle for artists in Iran to produce expressive content, Panahi represents the resiliency and commitment of Iranian artists to perform their craft; Panahi’s first film produced during his ban, This Is Not A Film (2011), was smuggled out of the country in a cake. Asghar Farhadi, has too, circumnavigated the restrictions of the regime to find critical acclaim and international success, including receiving two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film. Farhadi’s films are not docile, despite what the regime’s permission might imply, and are often critical of Iranian civil life. Farhadi is able to gain government approval because his criticisms are much subtler than what would trigger censure by the officials. By not centering in on Islam or the government, but instead on the nuanced hardships of life in Iran, Farhadi strikes a balance between criticism and approval.

In the contemporary art space, art was not quite as successful post-revolution, in part because a number of young artists either left the country or got stuck abroad without being able to return. Shirin Neshat is an example of an Iranian contemporary artist who was producing work at this time, but avoided returning to Iran for a number of years following the revolution. Much of the art that did get made directly after the revolution in the realm of fine art was more conservative, and steered clear of topics that would find opposition from the Islamic government. Slowly though, despite the tightening that happened directly after 1979, the art world in Iran became less austere. This relaxation began in the late 1990’s during the term of reformist president Mohammed Khatami. Artists like Farrah Ossouli worked in the vein of artists from the 1950’s and 60’s, who made reference to Iranian and Islamic cultural symbols in their work, with her appropriation of the Persian Miniature style of painting. (Fig. 10) Throughout the 2000’s the work of Iranian artists began to sell for high amounts at international art auctions, and the proportion of Iranian art sold at art auctions in places like Dubai steadily grew. Many Iranian contemporary artists like Shirin Neshat, incorporate specifically Iranian iconography into their works, or deal with themes pertinent to Iran. Neshat is an example of an artist who does both. Much of her work deals with the treatment of women in the country and uses images like the chador and the visual vernacular of the Persian alphabet to create images that comment on modern life in Iran for women. Neshat is not alone in her participation in creating visual art that is distinctly Iranian. Farhad Moshiri works in a tradition that is rooted in Pop Art, but often deals with Iranian symbols, language, and subject matter. His glittery, Swarovski crystal studded piece عشق (Love), is simply the Persian word translating as love. In 2008 the piece sold for over a million dollars at auction.

One reason that Iranian art has gained so much steam over the last two decades could be because a large number of Iranian artists have developed distinct styles that, though often look very different from each other, are thematically related by notions of Iranian identity. This identity comes through both in content matters such as politicization, gender issues, or critiques of theocracy, and in stylistic matters such as the employment of Iranian and Islamic visual vernaculars. This distinctiveness is appealing to international audiences. Iranian artists’ increased international presence has also grown the appeal for, and awareness of their works. Younger gallery owners like Hormoz Hematian, who opened the gallery Dastan’s Basement in 2012, have nurtured young artists of the most recent generations and supported them onto the international stage. Hematian and other gallery owners offer representation to young Iranian contemporary artists at international art events like Art Basel in Miami, and for the last decade there seemed to be another boon in the Iranian art world. Hematian talks about how now artists are not really worried about censorship from the government, because the artists he and others represent are well aware of what not to put in their art and the ways around representing sensitive topics.

Last year, in 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that he would be reimposing sanctions on Iran following the U.S.’s withdrawal from the JCPOA. The Iranian rial subsequently dropped in value by over half. Some in the Iranian art world are concerned that this huge devaluation in the Iranian currency, coupled with an increased difficulty of doing work with the international art establishment, would cripple existing Iranian artists, and squash those who are not yet established. It still remains to be seen, however, what exactly will come from the reimposition of U.S. sanctions on Iranian artists. In January of 2019 the 10th edition of the Tehran Art Auction netted several millions of dollars, with artists like Monir Farmanfarmaian and Hossein Zenderoudi each selling works for around a million dollars each. Though this does represent some resiliency on the part of the domestic art market, Hematian in 2018 expressed greater concern about Iranians’ ability to maintain a presence abroad, having greater faith in the domestic art market. Only the coming months will tell whether or not his, and others’, fears hold water.

Images:

Fig 1 (C/O British Museum)

Fig 2. (C/O Khan Academy)

Fig 3. (C/O British Museum)

Fig 4. (C/O Business Wire)

Fig. 5 (C/O Calouste Gulbenkian Museum)

Ibrahim's (Abraham's) sacrifice. Timurid Anthology, Shiraz, 1410-11

Fig. 6 (C/O Encyclopedia Iranica)

Geomancer (Rammāl), 1892, Oil on Canvas

Fig. 7 C/O MOMA

Untitled, 1963, Dried earth on canvas

Fig. 8 C/O Christies

Heech on chair, 2007, fiberglass

Fig 9. The Cow, Darius Mehrjui, 1969

Fig 10. C/O Christies

Farrah Ossouli

The Birth of Venus, 2007, gouache and gold on card